In a sublime setting at the Southern end of the Golden Valley, Dore Abbey is one of only two Cistercian abbeys in England still in use as a parish church. The abbey was founded by Robert of Ewyas in 1147 for Cistercians from Morimond, although nothing identifiable remains of the original building. The present church was begun around 1175 and was built in two campaigns, finally being consecrated in 1275. It represents well the transitional moment in English architecture when Norman Romanesque gave way to what became Early English Gothic.

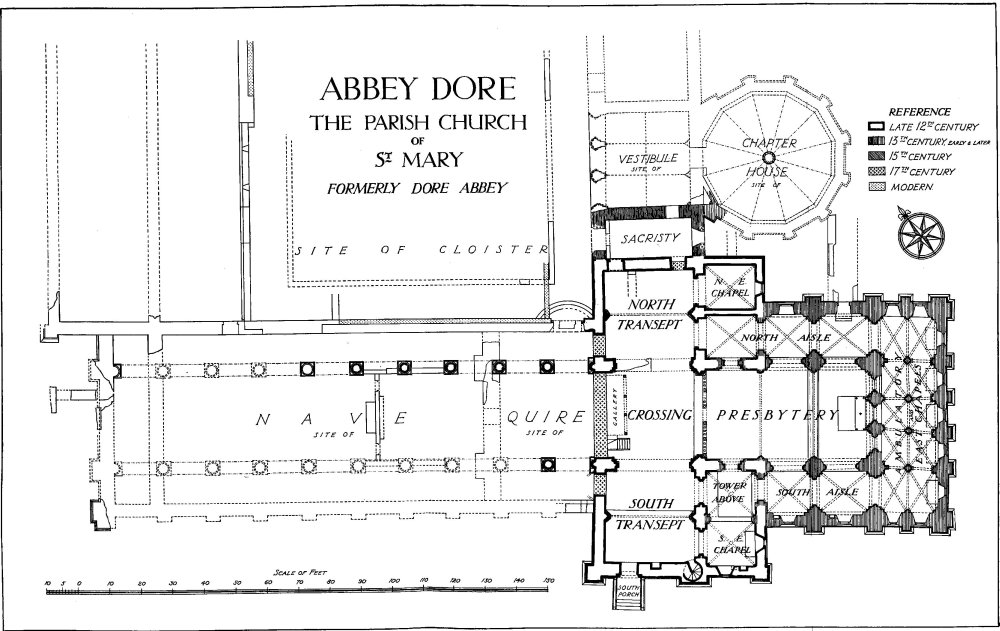

At the Dissolution in 1536 the abbey was sold to John Scudamore, who demolished the monastic buildings, the nave, pulpitum and choir, selling off the stone and roofing timbers. The rest was left to decay, only to be rescued by Scudamore’s great great grandson, John, first Viscount Scudamore in 1633. The restored church, fashioned from the transepts, presbytery and the Eastern retrochoir or ambulatory, was refurnished in a style influenced by William Laud, then Bishop of London and contains spectacular woodwork by local master craftsman John Abell. The tower, in an unusual position at the junction of the south transept and the chancel, was added in 1633 by David Addams of Ross on Wye, reusing stonework salvaged from the nave. There were further alterations in 1700, when the elegant West gallery was added, and significant repairs were undertaken between 1902-3 and 1906-9 under the supervision of Roland W. Paul. Paul re-ordered the church internally and undertook extensive archaeological exploration of the entire site in order to determine the plan of the church and the monastic buildings. Little of any consequence has happened since Paul’s sensitive work, although there have been by necessity extensive roof repairs. Today’s haunt of ancient peace also belies the fact that until 1953 the GWR’s Golden Valley branch line railway ran within yards of the church .

Externally the missing nave can be traced. There are two columns, one with a surviving arch, and the springers and corbels that once supported vaulting. The blocked crossing arch has a lancet window that came from the nave clerestory. The long stone churchyard wall marks the course of the North wall of the nave.

The church in 1891, with seating in the crossing

The transepts and crossing in 1840

Today’s visitor enters by a door in the South transept, which is sheltered by a sturdy timber porch of 1633.

Today the transepts and the crossing are one vast open space

The font dates from the 1633 restoration. The gallery was installed in 1700

The transepts, the crossing and the presbytery have fine flat timber ceilings of 1633 by Abell, replacing lost vaulting, but the two aisles and the spectacular double bay ambulatory at the East end retain their original vaulting.